We'd invented a new technology, and we wanted to tell anyone who was willing to listen. This is the story, step by step, of how we took the HOWL from idea to market...

Howdy folks!

That November trip to Utah showed us how grim the future really is for campfires.

Wood fires, even in the off season, are becoming a thing of the past. Drier forests and hotter weather makes them risky during more and more of the year. At the same time, traditional propane fires are a completely terrible replacement:

- They’re not warm

- They’re a pain to transport

- They’re not durable and they feel like they won’t last

Things were bad. We knew we would need the campfire experience for the rest of our lifetimes, and after we die, future generations will too.

So we wondered: “How do you make a propane fire pit that’s not a compromise to a wood fire?”

A propane fire's packability and durability problems seemed fairly solvable. Just use good design so the tank and fire pit are stable. Then use bomber materials to make it durable. Voila.

But making a propane fire pit *actually warm*? Now that was going to be more complicated. No one had ever done it before, and we didn’t know if it was possible.

All we knew was that we had to replicate the heating effect of wood coals. And we knew coals deliver heat through “radiant heat transfer.”

But this was the problem. We’re car guys, so "radiant" immediately made us think of radiators. We just assumed that radiators actually radiate heat (it's in the name!), and that assumption is all over our early sketches.

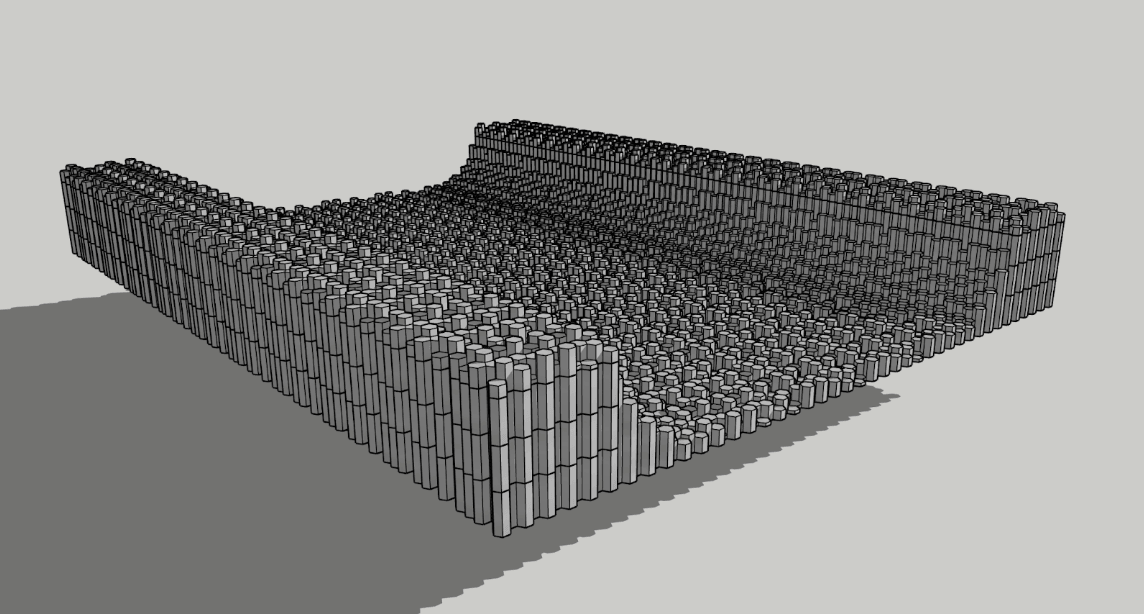

[Early engine-block style fire pit with "radiator" fins and modular repeating parts]

These drawings have fins like Harley engines, which make a lot of surface area, just like other radiators. This made so much sense to us at the time, but we couldn’t have been more wrong.

[Early hexagonal modular cast design, with stackable repeating parts.]

What is radiant heat, actually?

It turns out the car part we call a “radiator” doesn’t actually radiate heat. Radiating means shooting out rays of heat through the air, or through space, just like the sun. And that's something a car radiator doesn’t do. At all.

In fact, most of the things we call “radiant,” like radiant floors, actually never use radiant forms of heat transfer. And that really makes things confusing.

What car radiators actually do is use “conductive heat transfer.” They (or their fluids) touch hot parts of the engine, and that contact "conducts" heat away from the engine. Then the fins of the radiator touch the cool air, which "conducts" the heat into the air, making it hot.

At no point are there any rays of heat coming off a radiator.

The funny thing is that, on some level, we even knew that. But in our car guy minds, dissipating heat through fins into the air still sounded great. So we spent weeks thinking up propane devices that would make hot air. It was like something in our brains glitched.

We knew hot air couldn't make you warm outside. We knew that the problem with all propane fires is that they only make flames, and flames make hot air, and hot air just rises and blows away. We knew that was why we were always so cold in burn bans.

We even knew that heating up fire pit decorations like glass beads or lava rocks only transfers heat into the air, which again, just rises and leaves you cold.

Yet here we were, thinking we were smart, while drawing elaborate new ways to make... hot air.

We needed help.

[Our finned, V-Twin Halfpipe design with BarCoal on-off button, A-Flame slider control, carry handle and folding legs]

MIT Engineers showed the way to a hot propane fire pit

After an embarrassing number of completely wrong designs, we had some very smart engineers from MIT tell us that we needed to emit *actual* radiant heat. You know, in the form of radiant rays. Like the sun.

They also pointed out that we couldn’t just shoot out any old rays. These had to be very specific rays at very specific frequencies in the Infrared spectrum, if the human body was going to be able to absorb them.

They taught us one of the miracles of wood coals.

Coals emit Infrared rays in two distinct frequencies, both of which are rare resonant frequencies of water molecules. Water absorbs the rays of wood coals incredibly efficiently. And since you're made of water, wood coals are one of the best things on earth for making you warm. No wonder humans love being gathered around fires.

But that left a major question. How do you make these very specific frequencies of IR light with a forest-safe propane system?

That secret will come in the next email. Until then...

Keep carrying the fire,

– Randall, Kelly, Nicholas, and Alex